Soleimani’s Role in Defeating ISIS: Field Realities vs. Western Narratives

DID Press: The defeat of ISIS in Iraq and Syria cannot be viewed merely as a limited military success. It represented the clash of two competing narratives: the field narrative, which emphasized the decisive role of General Qassem Soleimani and the “Axis of Resistance,” and the Western media narrative, which sought either to minimize that role or push it to the margins. Understanding this narrative gap is essential not only to grasp the realities of the war against ISIS, but also to analyze how soft power is produced and global public opinion is shaped.

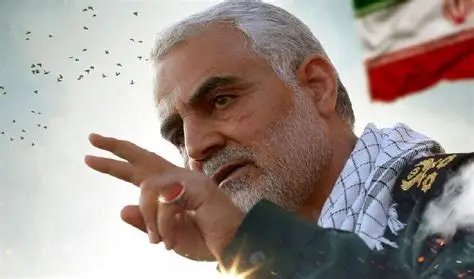

In the field narrative, Soleimani is regarded as the principal architect of ISIS containment. His presence on front lines — from Amerli and Jurf al-Sakhar in Iraq to Aleppo and Al-Bukamal in Syria — went beyond the duties of a conventional commander. He acted as the vital link between regular armies, popular mobilization forces, and resistance groups, forging a genuine operational coalition. Unlike Western “symbolic coalitions,” this alliance delivered results on the ground. The lifting of the siege of Erbil, preventing the fall of Baghdad and Damascus, and the ultimate collapse of ISIS’s so-called caliphate would have been difficult to imagine without such coordinated efforts.

By contrast, the Western media narrative recast the fight against ISIS largely within the framework of the U.S.-led international coalition. In that narrative, Iran and Soleimani were either erased from the story or depicted as peripheral — even obstructive — actors. Western outlets often portrayed ISIS as a threat neutralized primarily through precise airstrikes and sophisticated intelligence operations, despite battlefield evidence showing that without capable ground forces and local resistance networks, those strikes had limited decisive effect.

This narrative gap stems from deeper strategic contradictions. Acknowledging Soleimani’s central role would mean admitting the limitations of Western intervention models in West Asia and recognizing the relative effectiveness of a localized, network-based approach not dependent on extra-regional powers. As a result, Western actors preferred to claim ownership of victory while simultaneously framing Soleimani as a “threat” within their security discourse.

The implications extend beyond media framing. Globally, the Western narrative helped shape perceptions among distant audiences. Regionally, however, the battlefield narrative maintained dominance. Images of Soleimani alongside Iraqi and Syrian fighters became symbolic capital that strengthened the legitimacy of the resistance axis and challenged Western claims of a sincere war on terrorism.

Ultimately, Soleimani’s role in the defeat of ISIS must be analyzed not only militarily but narratively. On the battlefield he contributed to ISIS’s collapse, and at the level of meaning he disrupted Western narrative dominance. This fusion of battlefield success and narrative challenge helps explain why his elimination became a priority for Washington: the issue was not merely a commander, but a narrative that questioned the legitimacy of the Western security order in the region.