‘I’ll be sacrificed’: The Lost and sold Daughters of Afghanistan – part One

Child marriage, lack of education, financial desperation – a year on from the Taliban takeover, what does the future hold for women and girls?

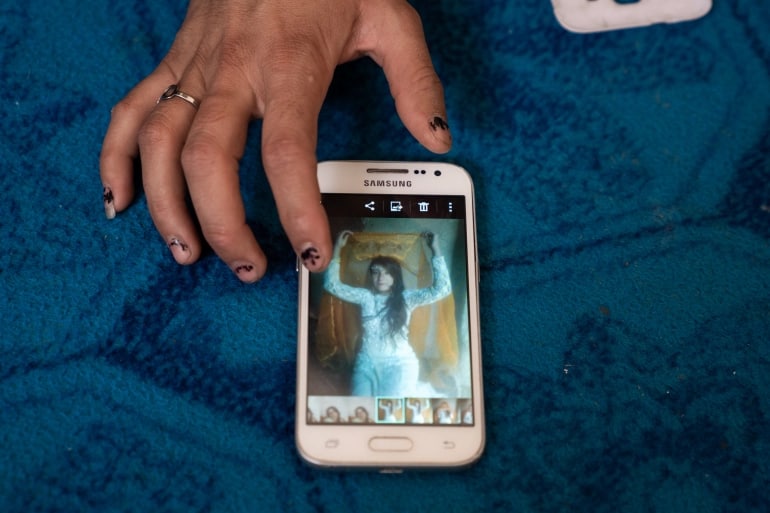

The last time Aalam Gul Jamshidi saw her daughter was the night the 16 year old was married off to a man more than twice her age.

Aziz Gul looked radiant in a sequinned, white wedding dress and a bright yellow headscarf, but there was fear in her otherwise solemn expressions. “If I go there, I’ll be sacrificed,” her mother remembers her daughter pleading that night last October.

Aalam Gul had a sinking feeling but convinced herself it was just nerves. Aziz Gul’s marriage had been arranged four years prior and now that the time had come, she knew it was her duty to encourage her daughter into a new family.

In Afghan culture, once a female marries, she moves in with her in-laws. Aziz Gul left her family’s home in Gozar Gah, a suburb of Herat, and moved to her new husband Musa’s home in Jawand, a rural district some 200km (124 miles) away – too far for her family to visit easily.

Five months later, the phone rang. It was Musa’s father calling to tell Aalam Gul that her daughter had been killed. Her naked body had been found in a forest just outside the village where she had lived with her in-laws. Aziz Gul had been beaten and shot four times in the back.

She was 17 years old and four months pregnant.

Aziz Gul’s family – ethnic Jamshidi Aimaq, self-described Tajik Arabs – are originally from Badghis province. They moved to Herat during the height of the conflict between the previous government and the Taliban, which retook control of the country after United States and NATO forces withdrew in August 2021.

Before the family left, when Aziz Gul was just 12, her parents agreed to marry her to Musa when she turned 16 – the minimum legal age for marriage in Afghanistan under the previous government. The Taliban has not mentioned whether that minimum age has changed. In exchange, her 26-year-old elder brother Aminullah would marry Musa’s 18-year-old niece, Shakar.

Across Afghanistan, it is common for children – particularly girls – to be married. Families arrange marriages to pay back personal debts, settle disputes, improve relations with rival families, or simply because they hope marriage will offer them protection from the worst extremes of economic hardship, and social and political upheaval.

Though child marriage is not thoroughly tracked in Afghanistan, with gaps in concrete, holistic data about the number of children affected, UNICEF has reported children being sold as young as 20 days old for future marriage, with girls disproportionately affected.

Now, amid spiralling poverty and the difficulty of finding sustainable jobs – only five percent of Afghan families have enough to eat daily, and inflation for essential household goods is at 40 percent (PDF) – even more families are struggling.

Many are making desperate decisions to survive, including selling their children – specifically young daughters – into marriage or arranging their marriages in order to receive a dowry or mahr. The dowry, paid by the groom to the bride’s family, is a traditional practice in all marriages in Afghanistan, but more families are now seeking this to help them survive difficult financial times.

‘Fits of rage’

Aalam Gul had three sons and four daughters; Aziz Gul was her second-eldest daughter. She was always close to her mother, and would typically speak to or at least message one of her family members every day.

The day after she was killed in March, her in-laws told her parents that she had run away after they were concerned when she did not return their calls. Two days later, a local farmer discovered her dead body in the forest and alerted local authorities in Jawand, who began an investigation. That same day, after villagers started talking about the incident, Musa’s father admitted to her family that she had been killed.

Soon after, Aziz Gul’s grief-stricken parents embarked on the several days’ journey to Jawand to bring her body back to Herat. “We [collected] her body [from local authorities] about three days before the month of Ramadan,” Aalam Gul says, in tears. “[The killer] just threw her body outside in a forest, as if she were not a human being. I wonder how scared she was.”

Musa and some of his relatives quickly pinned the murder on his mother, Aziz Gul’s mother-in-law. They claimed she was frustrated at her daughter-in-law for not knowing how to do housework, started beating her, and shot her in rage. But Aziz Gul’s parents suspect it was Musa. During the months the two were married, Aziz Gul and other relatives discovered that he was an opium user who would easily fall into fits of rage.

Aziz Gul’s father, Khaja Abdul Ghafor Jamshidi, says they received investigation reports from the local Taliban police authorities in Jawand. Musa and six other known criminals were questioned a few days after her body was found, but the authorities told Khaja Abdul there was not enough proof to make any arrests, and the killer’s identity remains unknown.

Eventually, the local Taliban chief in Jawand decided that this was an issue to be solved between the two families, and told Khaja Abdul that the case was closed. But it was the family’s word against Musa’s.

When Aziz Gul’s family tried to appeal to the larger, more authoritative Taliban police authorities in Herat, the case was sent back to local officials in Jawand.

According to Khaja Abdul, Musa was influential within the Jawand district. The region is considered lawless and not entirely under the control of the Taliban commanders in Kabul. Different factions operate in decentralised silos and do not necessarily communicate, follow the same rules, or want to intervene in other jurisdictions.

In Afghanistan, domestic violence cases rarely make it to the courts, including under the last government, and are often left unsettled.